Trash Picker or Beautifier | Election Day reflection

This morning I took a stroll around the lake near my home in San Antonio. One loop around amounts to a mile or so and on the path I come across burly men walking their pit bulls, elderly couples and young joggers. Big trees line most of the lake and ducks roam around the lawn. People smile and say, good morning.

On the northwest side of the lake, though, garbage gathers into a canal. There, I spotted two men in a simple boat gliding across the lake. With their nets, they scooped up styrofoam cups—San Antonio loves its styrofoam—,plastic bags, and even a stray piece of lumber, which they dumped into big plastic bins.

The lake itself is manmade and it could be bigger, there could be more trees, maybe even a garden. It could be better but it’s what we have. For now these men, who didn’t appear to work for the city, are making our little lake a bit more beautiful, liveable. There will be more trash for sure, perhaps due to ignorance or laziness or because the park needs more trashcans. Trash shows up for countless reasons.

I imagine a person might consider these men trash pickers, chumps who clean up after others, when more trash will surely follow. And, I could understand if folks ignore them or wave them away, after all real solutions and change takes time and steady effort. I suppose such decisions in perception are a matter of a person’s sensibility or character or perhaps. it depends on the weight of cynicism and despair. I couldn’t tell you. But, I do know we face those decisions every day. On some days, it just counts for more. Y’all have a good day.

Postcard Becomes Mirror-the desert sound

In late January, I returned to West Texas, to Terlingua at the invitation of an innkeeper who offers space to writers and artists. As these things often do, the entire experience came together, through a delicate mix of resolve and serendipity.

The Big Bend area has come to occupy special place within me. Last summer, I traveled to Marfa for six-week writer’s residency through Lannan Foundation. At the end of my stay, I was scheduled to deliver a presentation at the Marfa Book Co. Even though I had the basic outline down, I couldn’t quite get hold of the soul of the story I wanted to tell and I wasn’t going to find it at the desk. I drove some 100 miles to Big Bend and went on a long hike and then I heard it.

My writing often begins with a sound. The beat is often triggered by some sort of activity or motion–hiking, running, cooking, driving, etc. In the months since, I have returned to the Big Bend area several times and each time, I have heard the words I needed. Maybe it’s the long drives or the long hikes but, each time the desert manages to channel my restlessness.

While on the visit in February, I had hiked deep into a new path when I began to hear words that seemed like the beginning of a postcard to someone who had been with me days before but had since left.

I wrote them all down but stalled at the ending. It ended by saying I was meant to walk, to remain in motion, and the words had the feel of resignation. That ending made a postcard to another became a condemnation–of myself. I was meant to walk, to leave to continue.

At the end of April, a few days before I returned to Marfa, I woke from a dead sleep with my ending. I never sent the postcard but when I arrived in Marfa, Tim Johnson, a brilliant and gracious writer and friend and owner of Marfa Book Co invited me to read it as part of their 15 seconds with a poet series.

Please take a look and thanks for reading and watching.

Mother Duck and her Brood Decamp to Central Park

One afternoon in May, shortly after lunchtime, Mother Duck broke loose from Morningside Park with her eight ducklings in tow. Four people, who until then were strangers, came upon the family waddling down West 114th street, toward an unknown destination. We tried to turn them back to the Morningside Park pond, which was only one block away, but Mother Duck was not interested in that lesser real estate.

Someone brought a cardboard box. The plan was to box them up and deliver them back to the pond. But once inside the box, Mother Duck panicked. With that we started off, four people, plus a few others who joined along the way, escorting eight ducklings and Mother Duck down Frederick Douglass Blvd (8th ave). We had to keep the ducklings from wandering onto the sidewalk grates with their gaping holes big enough to trap a duckling. And we groaned when the ducklings resorted to lapping up the gutter water. One woman, who was late for work, video taped the expedition to later explain her tardiness to the boss.

Mother Duck then ditched the sidewalk and hit the street. We formed a perimeter around the migrating family to keep the passing trucks, cars and city bus at a distance. Cops pulled up and suggested we take them back to Morningside. She doesn’t want to go, we told them. That’s as much help as we got from the NYPD. Then a bus driver pulled up and said, I’ll take them to Central Park! They waddled, we walked, for four long blocks. I called the city and the folks at Central Park promised to send the rangers, but they never arrived. When I called back, we had reached 110th street so the operator said, you’re already there why do you need help?

110th street is a turnabout which meant we had to form a human line to block two streams of incoming traffic from entering the circle so Mother Duck and her brood could waddle across. Once they cleared the street, the ducklings struggled mightily to get up the stair by flinging themselves into the air. A statue of Frederick Douglass waited in the center. It seemed doubtful they could manage the other four stairs and so we scooted them around toward the ramp. Cars stopped, pedestrians snapped photos, construction workers stared, no one honked and everyone smiled.

I’m happy to report that nearly an hour later, Mother and babies entered Central Park. Such a fine day in Harlem.

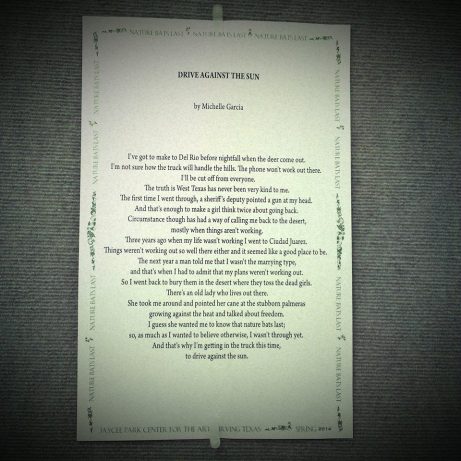

Driving Against the Sun: a Texas art exhibit

In March 2014, I had the great honor of contributing a monologue to the group exhibit, “Nature Bats Last” in Fort Worth. Writers were paired with visual artists who render an image from our words. My piece was based on recent border experience, although the gun to my head was a few years back.

The curators expect to take the show on the road. I will include updates as they come in.

The things I love don’t belong to me–life in Mexico City

There’s a bottle of Jimador brand tequila, half full, in the kitchen, the remains of a conversation about the Mexican student movement. But I didn’t buy it. The bottle of J&B holds just one swig and I never touched. It landed in my kitchen after a book party I didn’t attend, brought over by someone who doesn’t live here, but did for a few weeks while I was in New York and who unraveled my narrative conundrum. The near empty bottle of red wine, originated in a vineyard near Monterrey, in northern Mexico, and arrived at my home via a friend reporting on ‘election campaigning in areas controlled by organized crime,’ the assignment itself mocking any notion of democracy. The wine, too sweet to drink, made for an excellent stewed beef with vegetables, prepared by that reporter who covered the story, scored the wine and who rode off in a cab driven by a spy for a local crime cell.

The sky blue antique ashtray sitting on my refrigerator, in the early months held the bullet shells that I collected after an off duty cop in Guanajuato rang in the New Year by firing his pistol into the air. It was later filled with countless cigarette butts, the result of long talks about the dark topics that often dominate discussions and precipitate clandestine smoking. Death, disappearances, corruption, impunity. The ashtray, not mine, is now empty.

Just beyond the kitchen, in front of the door to the back patio that I mainly use to store the trash until the garbage truck comes around, stands an oversized slightly tacky arrangement of artificial flowers with a musky odor purchased from a 10 year old boy. He made the rounds at a steakhouse where some 30 journalists had gathered after learning strategies for coping with trauma. He slapped hands with the men, flirted with the ladies and flashed a wily smile, charming his way into selling five arrangements. In truth, he was welcomed as an unscheduled dose of relief.

A yellow rose that I presented to a man who helped me find towels when I arrived and who later held my hand occupies the center place in my living room. The rose, now shriveled, made him smile, and it will stay in the glass art deco vase as long I can see faint strains of life or as long as I’m still here.

The sheets aren’t mine, nor the down comforter, nor the massive white desk of pressed wood where I spend all of my time. They stay behind, along with the spices and cheese grater I bought, my only contributions to this apartment. Within 10 days all of it, along with the plants and trees I have tended to, will be off limits to me. I have nothing left in hand from the late night whispered conversations in the garden about the teachings of love that defy intellectual exercises. No memento from the nights that we searched the sky for stars, and imagined shaping stories from the void left by the 10,000 disappeared and what their absence says about the lies told about what some call a war, and how we tolerate those lies. I failed to record those conversations and I failed to figure out why nights out in Mexico City always seem to end after 3 a.m. But I have noticed those are the conversations that become plans realized, editorials written, alliances formed.

I also failed to keep my bamboo plant alive, it was overcome with a plague and the remedy—shared by the friend who bought the tequila– involves mixing tobacco with water. I haven’t tried it, I’m not good at concoctions. Even the hummingbird spurned the nectar I prepared for her. There’s no possible way to preserve these things or even say good bye, not to the hummingbird that tiny wonder who snaps me out of my obsessive thinking with the sharp flap of her wings announcing her arrival. She is simply an inspiration, as is the glow from the evening sun that radiates from the stone walls in the garden. There can be no good-byes for things that make me stop and look, things that last for a moment, things I can’t hold in my hands.

The things I love I leave behind, they don’t belong to me. I am empty handed after my time in Mexico City. Progress was slower than I expected, ideas I once thought brilliant soon seemed untenable and distracting and were abandoned. The book flourished but remains unfinished. But I love the things that belong here all the same because they are reminders of moments that forged a deep appreciation and respect for loosening my grip, claiming nothing as my own, and allowing truth to reveal itself —the focused surrender to the work. For that bounty, and the people who brought it to fruition, I am grateful.

Room to Write

From what I understand I lost consciousness in less than a minute. The same anaesthetic that, along with other things, killed Michael Jackson dripped into my veins yesterday afternoon while a doctor took a look-see to discern the source of a mystery pain that has persisted since the Fall.

I’m told that most people feel dazed when they “come to,” but at the moment of consciousness I experienced what you might call a “creative vision” a great clarity that left two vivid thoughts in my mind—the desert and a desire to write.

I visited the Sahara desert over a year ago and produced a video report on the Sahrawi refugees and yet, the fact that I haven’t written anything about them nags at me. Maybe because until I write, I won’t know exactly what happened, what I learned. The pile of notebooks left unstudied, my experience unexplored. It’s as blank as this page was when I began.

At the moment of consciousness the mental circus quieted and an inner truth was revealed-without the exercise of writing, my emotions run amok, the circuitry of my reality becomes tangled up with feelings and impulses and I become lost. I suspect those unrestrained, unexpressed emotions have contributed to my mystery pain. And I can’t help but wonder if an undiagnosed need for the journey that defines ‘writing’ ails not just me but many of us. Could we call it a social ill?

Sure there are plenty of venues for expressing what one thinks, one feels, their sexual desires, fetishes, the daily outrage. But I’m talking about the journey, feeling and researching your way from point A to point B and not knowing where that is when you start out. I’m talking about being made to feel uncomfortable because what you thought you had all sewn up, your take on reality, is suddenly shot to hell.

Joan Didion in her speech “Why I Write” said: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want to what I fear.”

Writing forces me to acknowledge what I don’t know, demands you figure things out, sculpt your thoughts, observe them, challenge them, and make peace with thoughts and emotions. I don’t claim to excel at any of this, in fact, this may be the most poorly written piece of garbage I have churned out to-date. I’m simply describing the painful process that forces me to be with myself, and then nakedly and at times publicly reveal what I learned. Over a leisurely dinner recently, a friend read aloud a selection of Salvadoran poetry. I marveled at the constant in many of the pieces, the observance of the poet from a distance, the creation of space between the self and the narrator.

Entra una mariposa por la ventana.

Y pienso que es Chuan Tzu

Que se sueña convertido en mariposa.

Pero a medida pienso la mariposa vuela

Y revuela en el cuarto vacío

Y yo no estoy.

–Alfonso Quijadurias

Working on Tell’em Who You Are demands a similar effort, it has forced me to delve into private places, and kick up emotions all toward drawing the blood that becomes the story. Through loss and circumstance I am freeing myself from my own narrative to discover anew my childhood home, my ideas of home and family. Shooting injects distance between what I believe I know and what I see, to analyze the image and its meaning, images that are as familiar to me as my own reflection. In March I spent an entire afternoon shooting South Texas wildflowers and reflecting on how a concrete bench under a rustling oak tree viewed from one angle but not any other can provoke a deep nostalgia in my heart.

I’m not sure what I’m supposed to do with my discoveries, put them on a backburner somewhere until it’s time to edit? The images are recorded on a tape that just sits there giving me nothing, no outlet. There’s no process for thinking through what I feel. It’s excruciating. Maybe that’s the source of the pain. Maybe my stifled message has manifested itself as an attack on my very self.

Certainly over the last few weeks I have experienced a rush of wild emotions, mostly from a feeling of impotence about the events in Arizona while I’m stuck in New York. I want to know what’s going on, firsthand. I resolved to travel there later in the summer. Then, a Border Patrol agent shot a teenager in the head on the border between El Paso and Juarez and the story summoned memories of another dead young man, Esequiel Hernández. I was just out of college and working in Washington DC when I met his parents who had traveled from their home in the remote border outpost of Redford Texas to confront lawmakers about their son. Hernández was 18 years old, a high school student, and herding goats when he was killed by a U.S. Marine.

All these years later, perhaps thanks to shooting those wildflowers, I figured out that what I wanted to say back then, beyond my report on discrimination against Latinos, the failure to uphold the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, (yep, that went in too) that ended the U.S. Mexico War, what I was really trying to do was analyze his photograph. He was labeled the ‘goat herder’ in most press reports but in that photo I saw a young man who resembled the boys I went to high school with, boys with the FFA emblem stitched to the back of their denim jackets, boys who wore cowboy boots to class, the prom, and then later to the army enlistment office. There was an entire untold story about a place and a young man and a way of life out there on the border. Even now, all these years later, yes, I want you to see what I see, “listen to me, see it my way, change your mind,” as Didion said in the same speech. But I couldn’t get it out, not then, I was inexperienced in the art of reflection and the space was constricted by arguments about “border security.”

Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca was shot by a Border Patrol agent while or after allegedly throwing rocks at agents, a teenage kid living in a city where there’s not much for teenage kids to do, a kid allegedly known for smuggling migrants. There’s a whole story behind how he got to be on that bridge and a story about pulling the trigger. And while their stories are somewhat different, what rings true for both border tragedies is the restricted view we in this country have about the border. There is no space, no divestment from the circular arguments about border security, about the meaning of the border, no respite from the yelling and screaming, no escaping the ideological divide, a divide that’s built and fortified by people who know what they know and know how to rile up everyone else.

Yesterday as the anesthesia lifted I realized that without that space, without the journey, I easily succumb to self affirming beliefs, seek out evidence to prove my point, and allow a tornado of emotions to envelop me. While it may feel good for a while, inevitably it’s followed by the pain.